Welcome back to Soulful Thoughts, a collection of reflections on deeper questions of life.

After a long hiatus, I’ve decided to start posting my writing here again, as well as interviews with people I meet on this confounding and wondrous journey through life.

I’m also sharing shorter reflections and quotes on Instagram, and you can follow me at soulfulthoughts.writer.

As my first post on returning to the blogosphere, I’d like to share a piece of my writing that was recently published in a beautiful art and literary journal called Still Point Arts Quarterly.

The piece is called ‘Symphony of Silence’.

It was featured in the latest ‘Minimalist Wisdom’ edition of the journal, and is an expanded version of a post I made here some time ago.

I hope you enjoy reading the text below or at this link, or you may prefer to listen to the recording I’ve made.

Thanks for your continued interest and support.

space

Symphony of Silence

A Prayer for the Music of Life

“Everything we do is music,” the American composer John Cage once said. “Wherever we are, what we hear is mostly noise. When we ignore it, it disturbs us. When we listen to it, we find it fascinating.”

Born in 1912, John Cage was one of the twentieth century’s most original and influential artists. In a career that began in the 1930s and spanned sixty years, he composed nearly 300 pieces, ranging from early works that adhered to conventional rules of Western music to later works that were created using “chance” processes inspired by the ancient Chinese I Ching.

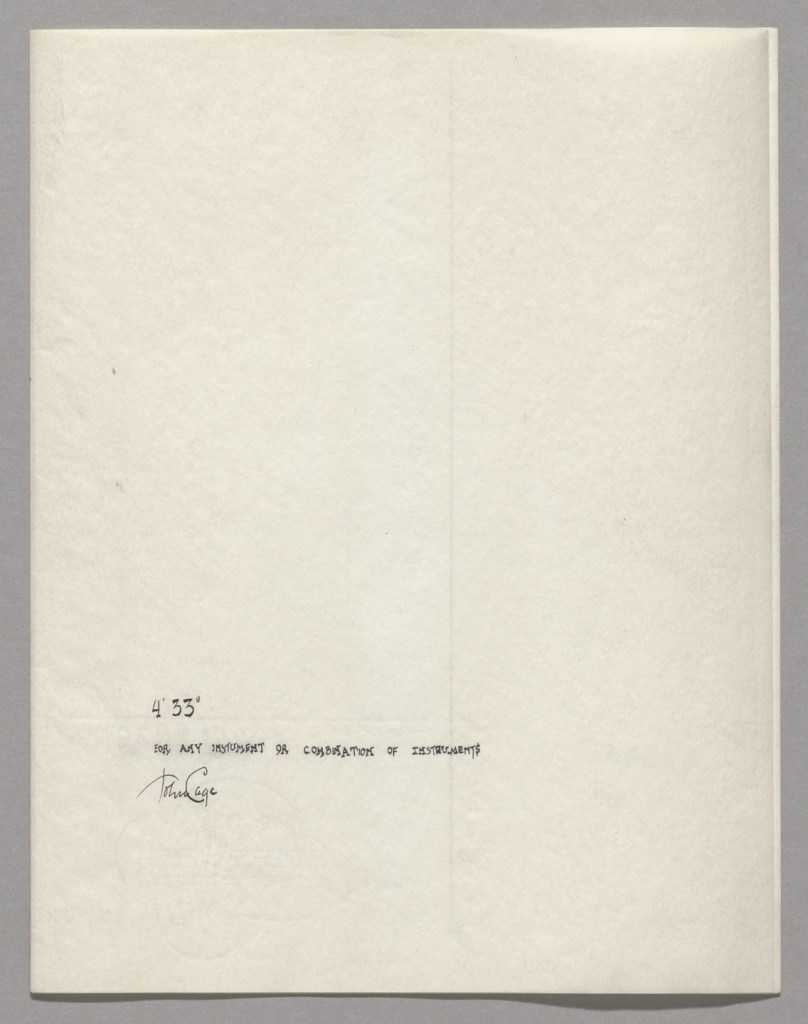

Cage is perhaps best known, though, for a piece called 4’33”, which reflected his keen interest in Zen Buddhism and became a pioneering work for modern minimalist music.

Pronounced “four minutes, thirty-three seconds,” the piece was first performed on a warm and rainy evening in August of 1952. The venue was a small auditorium—appropriately called the Maverick Concert Hall—near Woodstock, New York, about a two-hour drive north of New York City. The performer was American piano virtuoso David Tudor, and as he walked onto the stage and sat down at the piano, the audience waited expectantly.

To their surprise and disquiet though, Tudor didn’t play even a single note. Instead, he simply closed the piano lid, clicked a stopwatch, and rested his hands on his lap. After thirty seconds of silence, he opened the piano lid, paused, and closed it again.

After another two minutes and twenty-three seconds, he again opened and closed the lid, at which point some members of the audience walked out. Another minute and forty seconds later, Tudor opened the lid one last time, stood up, and bowed.

The premiere of 4’33” was over, and what was left of the audience politely applauded.

***

I came across Cage’s silent composition for the first time a few months ago when I was looking into the links between art and spirituality at a bookshop cafe in Sydney, Australia. I was immediately intrigued by the concept—was it postmodern? or enlightened? or simply ridiculous? I had a feeling of anticipation as I looked it up on Spotify and clicked play. 4’33” began.

I remember listening intently for half a minute or so. The silence was quite pleasant, even if I half-expected a note to sound or a chord to be played, despite having read a synopsis of the piece beforehand. Then I remember hearing a couple chatting at a table a few metres away from me … then the clanging of some plates in the kitchen … and then the low hum of cars driving by on an adjacent street. And then I became distracted and started scrolling online.

I don’t recall if I was checking my emails, looking through Facebook posts, or reading the latest news, but I do know that I kept scrolling all through the last four minutes of 4’33”.

What would I have heard if I’d been less distracted?

Maybe the rustling of the late-afternoon wind, a choir of cicadas starting up in the courtyard of the cafe, the footsteps of customers walking over to the counter, the pages of a book being carefully turned, or the sound of breath being drawn and expired.

There’s so much that’s beautiful and even wondrous in the soundtrack of everyday life. And yet, I pay attention so rarely, and it seems most of humanity does much the same.

Walk down the main street of any city and look at the people passing by. Without doubt, at least half—probably far more—will be glued to their phones and completely oblivious to their surroundings.

Have we lost the ability to appreciate the sounds, and even the people, that surround us—not virtually, but directly, tangibly, here and now? And have we lost the capacity for silence that spiritual traditions throughout the ages have said is the way to contemplation, wisdom, and peace?

Some seventy years after the premiere of 4’33”, these questions remain as urgent and timely as ever, and I, for one, regret having lost interest in Cage’s piece when I first listened to it. I regret not giving my full attention to those four minutes and thirty-three seconds that I spent sitting at a table at a bookshop cafe in Sydney. I regret not immersing myself completely in that small and never-to-be-repeated window of time, listening with every fibre of my being to the collection of sounds punctuating the silence.

“The commonest and cheapest sounds, as the barking of a dog, produce the same effect on fresh and healthy ears that the rarest music does,” wrote the philosopher Henry David Thoreau, whose writings greatly inspired John Cage later in life.

It makes me wonder if perhaps all of life is really a piece of music … a play of sound against a backdrop of silence … a creation of form in a formless void.

And maybe the emptiness at the heart of all things is really an invitation to appreciate life … like a blank score calling us to listen more attentively … an empty canvas urging us to look more perceptively … or an empty stage beckoning us to embrace the dance of life.

***

“Each of us has an image of John Cage’s silent piece,” write musicologist James Pritchett, “an idea—or many ideas—of what he created, why he created it, and what it means.”

Interestingly, Cage’s own feelings toward 4’33” evolved over time, as I imagine most genuine relationships with art—and silence—do. And yet, late in his life, Cage told his friend, the American composer William Duckworth: “No day goes by without my making use of that piece in my life and in my work … the important thing … is that it leads out of the world of art into the whole of life.”

John Cage passed away on August 12, 1992, forty years to the month after 4’33” premiered. In a New York Times obituary published the following day, he was described as “a minimalist enchanted by sound,” and the sounds he created during his life were eclectic and daring—from the percussive notes of a “prepared piano”, which had screws and bolts placed between its strings; to the echo of a “water gong”, a gong lowered into water while vibrating; to the high-pitched squeak of a rubber duck. And yet, it was in silence that John Cage’s voice was heard most clearly.

Fittingly, the iconoclastic composer originally had a different title in mind for a silent piece of music. It was, he said in a talk in 1948, to be called Silent Prayer.

Maybe he felt one could discern one’s inner voice—and hear, even, the voice of the divine—by quieting, at least for a time, the noise of the mind and looking deep into one’s heart.

For within our hearts, he believed, lies the “tranquility which today we so desperately need.”

May John Cage’s wisdom, then, draw humanity closer to the essence of life. And may I listen more carefully, and appreciate the symphony more generously, today.